|

|

www.classicbikes.co.uk Machine of the month - archive features! |

|

|

Honda CBX 1000 Rod Ker time travels......back to 1978 |

|

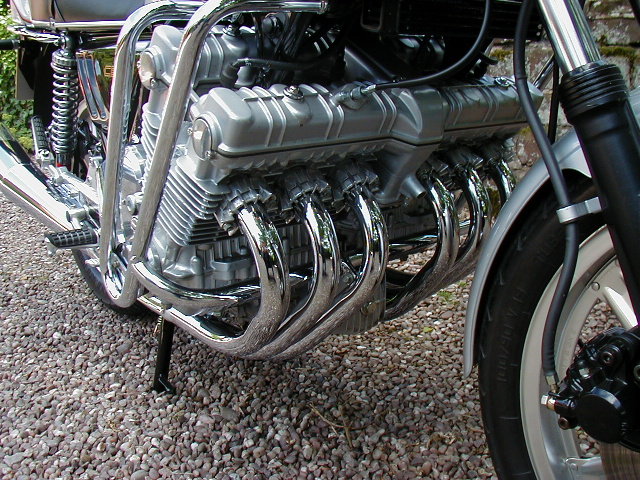

| "If you don't know what a Phantom jet fighter sounds like, buy a Honda CBX and have a fiddle with the exhaust system". Even as standard the six cylinder engine sounds amazing, but the story goes that during development a prototype was produced with silencers that made a noise uncannily like a jet (if a bit quieter). This was toned down for the production version because they thought riders might get too excited and tend to go a bit fast. Surely not! |

|

|

| It's a shock to realise that this happened almost thirty years ago now, when Honda's motorcycle designers had finally woken up again after spending far too long lesting on their raulers (all racist puns copyright, Benny Hill, 1975). Going back to the beginning, after a less than spectacular UK debut at the 1959 TT, Big H rapidly became a force to be reckoned with on the tracks. Multiple cylinder four-strokes were the house speciality, culminating in a series of technically outrageous fours, fives and sixes that performed, and sounded, like nothing else. Honda officially retired from racing in 1967, but the 1969 appearance of the road-going CB750 Four showed that a lot had been learnt. After that blaze of publicity, the early 1970s were the dark ages for the company in motorcycling terms. While plenty of innovative new cars were being released, the CB750 stayed almost the same for six years, giving other Japanese manufacturers (Kawasaki in particular) plenty of opportunity to improve on the transverse four theme. The water-cooled GoldWing launched in 1975 proved that they hadn't been entirely idle, even if plenty of people unfairly accused it of having more in common with a car than a motorcycle! Rumours had been circulating for some time, but the 1978 arrival of the CBX1000 stunned everyone. Created by a team headed by Soichiro Irimajiri, the very same man responsible for the 1960s racers, here was an all-new machine. With over 100bhp produced from 1047cc shared between half a dozen pots, here was the fastest, most glamorous bike ever. Even so, unfortunately for Honda, Benelli had launched their Sei some three years earlier - and it was especially ironic that the Italian engine was virtually a copy of the CB500 four with a couple of extra cylinders tacked on! |

|

|

| A superb Honda CBX1000Z restored by Chris Rushton Beyond the novelty of six cylinders, the Benelli really wasn't that clever. The CBX was in another league, although in 1978 there were still plenty of die-hards who couldn't accept that British twins were no longer the acme of perfection, so it probably wasn't given the reception it deserved. Gentlemen of the Press were keen to point out that the simple, cheap Suzuki GS1000 four was almost as fast in a straight line and had better handling. Meanwhile, if you wanted touring comfort and smoothness you bought a Yamaha XS1100 instead, with a big saving on purchase price and the benefit of shaft drive. With the greatest respect, as politicians say when they're about to kill each other, I think they completely missed the point. OK, the CBX probably didn't have a chassis that could do justice to 105PS at 9000rpm, but really, so what? All bikes of that era were fairly marginal in that respect, and how often does the average motorcyclist on the street use full power? Applying maximum thrust for ten seconds from a standing start would take a CBX to somewhere around 120mph. And consider that not many years earlier a rather famous racer named Mike Hailwood said that having more than 60bhp wouldn't get him round the TT course any faster - and that was when he was lapping at 100+mph! While Honda made much of the link with the old race bikes, the CBX really had nothing in common with them apart from the obvious. The race sixes were incredibly compact, not much wider across the fairing than a single. Great efforts had been made to keep the CBX narrow, too, but the engine still looked as big as a block of flats from the front, despite assurances that it was only about an inch wider than the CB750 four. Moving the generator and ignition from the ends of the crankshaft to a then novel position behind the cylinders helped, but meant that the engine was longer and had an extra hy-vo chain in the transmission. Moving up, instead of the single camshaft and two valves per cylinder that had served the 750, the CBX used twin cams, each split into two, prodding open no less than 24 valves through bucket and shim tappets. Hours of amusement at service time! To make the head more compact (they said) a hy-vo chain drove the exhaust cam, with a separate shorter one turning the inlet. |

|

|

| Feeding all this was a bank of six CV carbs, arranged in a vee formation to stop them interfering with the rider's knees. As this meant that the inlet tracts were different lengths, the pipes continuing into the airbox were configured in a way that evened out the differences. Clever stuff. With the cylinders tilted forward by about 30 degrees, and the extra jackshaft in the middle, the engine was bound to be long as well as wide. As Honda wanted to keep the wheelbase short, they therefore used a spine frame, so there were no downtubes to fit between the exhausts and front wheel. It also meant that the engine was given maximum visual impact! Whatever, at less than 59in from spindle to spindle, the CBX was fairly compact in comparison with some of its sumobike contemporaries. Unfortunately, although the frame looked promisingly rigid, Honda copped out a bit with the rest of the chassis. Alloy Comstar wheels with tubeless tyres were probably a lot better than the heavy cast lumps offered elsewhere, even if the rims were equally narrow. So far, so good, but at 35mm diameter, the fork tubes are considered incredibly weak and weedy now. This was actually fairly typical for 1978, but the swinging arm, a thin steel pressing carried in plastic bushes, seemed iffy even then. Hmm&ldots; perhaps they got Triumph to design that bit? Controlling the ups and downs was a new design of adjustable damper bearing the legend 'FVQ'. Honda claimed it stood for Full Variable Quality, which sounds fairly alarming, but everyone else knew them as Fade Very Quicklys, for obvious reasons! |

|

|

| photo from the "Cycle World" road test of April 1978 The styling and detailing was all much more promising, from the aircraft-inspired, orange-glowing instruments, to the chunky cast aluminium handlebars, to the sweeping lines of the petrol tank, which successfully managed to disguise its bulk. Although there were plenty of roadside pundits who thought the CBX was a bit pointless, no-one ever suggested it didn't look impressive. The bad news was the price: £2565 was an awful lot of money in those days (still is, come to think of it). In 1978 a Suzuki GS1000 was two-thirds as much and Yamaha XS1100s could be picked up for well under two grand. Running costs were equally high, because the six usually did about 15mpg less than the competition and was likely to be more expensive to service. Valve shimming wasn't needed very often, but you obviously had to be prepared for a big bill from your local 5 Star Honda dealer when the time came. Chains and tyres were also likely to wear out at a frightening rate. None of this matters much now, of course. The good news is that the CBX engine held together well, despite being very similar to the dohc 750/900 fours that were launched at about the same time yet tended to explode at regular intervals. There are various reasons why this might be so. For a start, the fours were more highly stressed because of their longer stroke, which could be why the con-rods sometimes snapped at high revs, possibly after a missed gearshift. The six's closely spaced firing intervals could also have given the camchains an easier life. Another theory is that typical CBX owners were just richer and looked after their bikes better. Whatever, for all the six's complication, there were always fewer complete dogs around. Although values fell quickly once the novelty had worn off, especially after Kawasaki launched the Z1300, and new CBXs could once be bagged for around £1500, secondhand prices never went into the bargain basement range. In the 1980s tatty CB750 and 900 fours were almost given away, but the sixes were always rare enough to be worth saving. The first Z model tends to be the CBX people remember and are prepared to pay the most for now, but the story didn't stop there. After a couple of years of declining motorcycle sales generally and dwindling interest in so-called superbikes, Honda decided to give the old girl a makeover. Using the same basic skeleton fitted with a detuned engine (which had already appeared on the American market A model), they added an upper fairing and a Pro-Link rear suspension, to create a... well, no-one ever seemed quite sure what the CBX-B was supposed to be! A tourer? Maybe, but it still had a chain to wear out and used far too much fuel, so why not buy a GoldWing instead? On the other hand, about 60lb of extra weight and reduced power made it less sporty than before. In fact, having been just about the fastest thing on two wheels, the Pro-Link was sluggish compared with the latest opposition. Even that wasn't quite the end, because there was also a C version (spot the new grabrail!). But by this stage few people really cared or noticed, and the CBX quietly disappeared in 1982. Ironically, it was effectively replaced by the CB1100RC, a hotted up expansion of the old CB900F. Honda conceded that the four could have been as fast as the six back in 1978, so we can infer that the CBX probably only existed to get two up on the opposition. I've been lucky enough to ride quite a few CBXs over the years, the first a few months after passing my test, as it happens. Compared with the fleet of rattly nails that I usually rode, it was a revelation. That one was a cherry red Z model, as sold brand new in 1979 for a lot less than the official list price. Having ridden several more similar bikes in the quarter-century that has passed since, I still prefer the original CBX, although it might be hard to choose between red and silver paintwork. Both look great, to me! |

|

|

| A 7 mile from new CBX 1000 Pro-Link But don't dismiss the Pro-Link because the opinion of an old bigot. The looks may be a bit dumpy (this is the CBX we’re talking about now), but there are compensations. For a start, it costs much less to buy, which is always an important factor in my book! While completely mint Zs change hands for over £10,000, a B or C in the same condition will go for only about half that. To illustrate the point, followers of this website will know that RWHS recently had a couple of 'new' zero-mileage Cs on offer for around £6000. Anyone lucky enough to discover a virgin CBX-Z in a cupboard under the stairs could virtually name their price. Even if money isn't a problem, it would also be possible to make out a case for the Pro-Link being a superior motorcycle on technical grounds. As I said, the original chassis wasn't too good. While the B's fairing tended to be its most unmissable feature, and the detuned engine caused disappointment, it shouldn't be forgotten that Honda had actually improved the running gear considerably. The Z's spindly 35mm stanchions were replaced by relatively stiff 39mm items, which helped enormously. At the rear, the swinging arm was stronger and better supported in the frame, while being part of an altogether improved springing and damping apparatus. Attached to the suspension were better brakes, wheels and tyres. And as I once discovered on a trip through the Peak District on a cool Spring day, the fairing made high speed cruising a much more civilised proposition. While the Z was certainly quicker in a straight line, in the real world the Pro-Link would have been faster, if a lot less entertaining! CBX-Z Specification Engine: 1047cc (64.5mm x 53.4mm), air-cooled, dohc 24-valve six, Keihin CV 28mm carbs, 103bhp at 9000rpm, 61lb/ft at 8000rpm, five speed gearbox Electrics: 12v alternator, electronic ignition Frame: steel, diamond spine type Suspension: front 35mm telescopics, twin FVQ rear shocks, adjustable damping/preload Brakes: twin 276mm discs, single-piston calipers, rear disc, single-piston caliper Tyres: 3.50 x 19 / 4.25 x 18, tubeless Dimensions: wheelbase 58.6in, seat height 32in, fuel capacity 4.4g, dry weight 550lb ---------------------------------------------------------- By Rod Ker, June 2005. Photos and text are copyright Classic Bikes Ltd. unless otherwise noted. |

|

Did you enjoy reading this?

Please e-mail us your views to rod@classicbikes.co.uk

INDEX & LINKS to other articles (for more of the same); - Kawasaki Z1-Z900 "Kawasaki's ‘New York Steak’ prototypes disguised as Honda CB750s were plying the roads of America by 1971, clocking up big mileages to make sure that everything was right first time. - Class of '76: Laverda Jota v Kawasaki Z900 - Kawasaki 500 Triples. "If Hannibal Lecter practised dentistry, this is the sort of noise that would be coming from his surgery"! - L-Plate 250s "Life was so simple for fledgling bikers back in the 1970s. Anyone capable of walking as far as the local No-Star dealer without tripping over his flares could buy a motorcycle, slap on a pair of L-plates, and wobble off into the traffic". - Honda CBX1000 "If you don't know what a Phantom jet fighter sounds like, buy a Honda CBX and have a fiddle with the exhaust system"!

|